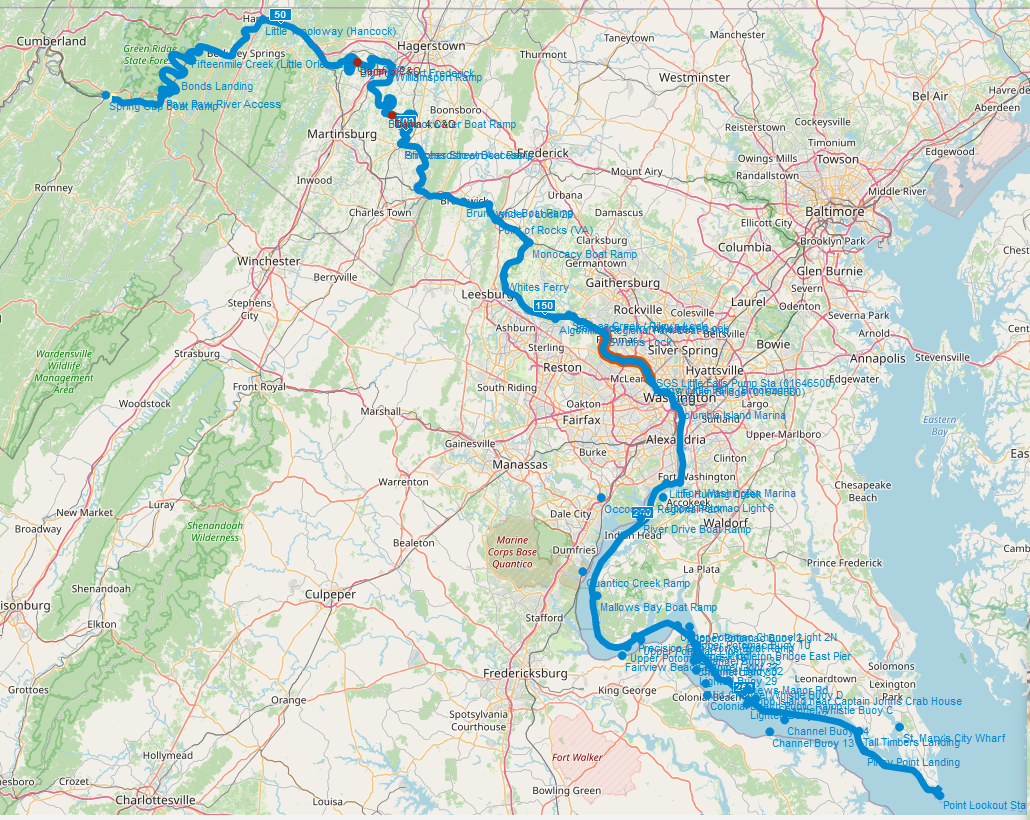

Potomac river 280 miles (west virginia, Maryland, washington d.c., virginia) Overall FKP Details

Potomac River

Route Proposed by: Nathaniel Gueltzau

Overall Fastest Known Paddle: TBD

1st attempt: Nathaniel Gueltzau, age 34, of Burke, Virginia. Solo male (supported) category. Started on 8/29/25, unable to finish due to low water, injury and safety concerns. Trip report forthcoming. Nate paddled 48 miles over 12 hours and 44 minutes starting at 7:35am on August 29th, 2025.

280 miles

Start: Confluence of the North and South Branches of the Potomac, Green Spring, WV

Finish: Point Lookout Lighthouse, Scotland, MD

Map resources from Visit Maryland

Route Notes from Nathaniel:

The official Potomac river starts at the confluence of the north Potomac branch and Potomac south branch. There are at least 5 major areas of rapids along the Potomac River, however 2 of them are class 3+ with Great Falls being between Class 4-5+ (depending on Water Levels) and I am not at that skill level and will have to portage around (FKP editor note: it is always acceptable to portage around rapids). There is the C&O canal that runs right next to the river for boats to pass and will use that or the tow path along the river (FKP editor note: this is acceptable). The end of the river is at point look out where it flows into the Chesapeake Bay.

Trip Report from Nathaniel:

I began my Potomac River run early in the morning on the August 29th, unloading my boat and gear at Old Town around 6:45 a.m. The first stretch required paddling three miles downstream just to reach the confluence of the North and South Branches, the official starting point of my route. My goal was ambitious but clear: maintain a pace of at least six miles per hour and cover a minimum of one hundred miles per day.

The air temperature was perfect, and conditions initially appeared favorable. Spirits were high, my gear was organized into totes for quick resupply, and my support crew was in place, ready to meet me at predetermined ramps along the way. Hydration and nutrition were dialed in, I relied on water, electrolytes, and nutrition packets, supplemented by snacks, so I felt physically set up for success.

At first, the river looked wide and manageable. But within the first five miles after the confluence, I hit the first of what would become countless rock gardens. The water was so crystal clear that I could see the entire bottom, boulders scattered across the width of the river. Fishermen lined the banks, and a few local high school boys cast their lines before heading off to class. The beauty was deceptive: what looked like a serene stretch quickly became an obstacle course of shallow water and jagged rocks.

These rock gardens forced me to exit the kayak repeatedly and portage across slick, uneven footing. Each time I tried to push through, the boulders lurking just beneath the surface punished my kayak and paddle. At least four separate times my boat struck unseen rocks so hard that it launched upward and flipped me over. Each recovery required dumping water from the boat, collecting myself, and gathering gear, though I was fortunate never to lose anything permanently in daylight. My primary carbon fiber wing blade paddle took the brunt of the impacts, ending up chipped and scarred from repeated collisions.

Even with the challenges, the river showed its wild side in unforgettable ways. I saw several bald eagles, ospreys, herons, and more turtles than I could count basking on rocks and logs. The water was so clear that fish darted visibly beneath me as I paddled. One of the most breathtaking moments came when six bald eagles began diving for fish in front of me at the same time, each one swooping and splashing the water with incredible precision. Deer appeared frequently along the banks, almost like sentinels at every bend in the river. These encounters were reminders of why I pursue expeditions like this; not just for the challenge, but for the privilege of moving through such raw, living landscapes.

I wasn’t alone out there. I crossed paths with at least six other paddlers during the day. Three were on a short camping trip, aiming to cover about seven miles before pulling off. We exchanged words of encouragement, and their presence added a sense of camaraderie. Later, I passed fishermen who were surprised but supportive to see a solo paddler pushing through such challenging conditions. The Potomac can feel vast and isolating, but those brief connections were grounding.

By the time night fell past 8 p.m., the temperature had shifted; the air cooled, and the river seemed to be warm. With darkness came a new set of difficulties. My GPS kept me aligned in the center of the river, but using a headlamp quickly proved unbearable; swarms of insects zeroed in on the light, filling my eyes and face. I resorted to paddling mostly in darkness, relying on the sound of water to guide me.

But even that was unreliable. Roughly every twenty minutes, a freight train would roar past on the nearby tracks, its noise drowning out the sound of the river and making it impossible to hear approaching rapids or rocks. It was eerie; just me, the dark water, and a sense of uncertainty that compounded with each mile.

The breaking point came during another rock garden portage in the dark. As I maneuvered across uneven stones, I slipped, twisting my ankle and falling hard to my left. I tried to catch myself, but landed with full force on my wrist, which collapsed, sending pain shooting up my arm as my elbow and face struck the rocks and water.

I sat in the river for a long moment, trying to gather myself. When I tried to stand, my ankle and wrist both screamed with pain. I eventually carried my boat far enough to relaunch, only to realize my paddle was gone. Fortunately, I found it downstream and kept going, but my wrist throbbed more with every stroke.

By the time I reached the next ramp, I was in a bad way. I sat there for nearly an hour, going back and forth in my head: push on and risk compounding the injuries, or pull out. I knew my personality. I would push myself beyond reason if I didn’t stop then. The pain, the worsening risks, and the reality of another long night ahead made the decision for me. Reluctantly, I called it.

In total, I covered roughly 48.1 miles, from the confluence down to Hancock. It wasn’t the distance I had hoped for, nor the finish I envisioned when setting out with dreams of hundred-mile days. But the lessons were real and enduring.

The Potomac taught me respect through hardship; low water, relentless rock gardens, capsizes, injuries, and the mental grind of paddling in the dark. At the same time, it gave me gifts: clear skies, perfect temperatures, healthy fuel and hydration, encounters with wildlife, and moments of connection with others on the river.

Calling it quits was one of the hardest decisions I’ve had to make, but it was the right one. Continuing would have put me at extreme risk for further injury, and that’s not a gamble worth taking. The river will be there another day, and so will I.

Pre-attempt Notes from Nathaniel:

He will be paddling a P & H Scorpio MKII HV Kayak and will be supported by Sergio Morales.

He writes “I first got into paddling in 2021 when I took on the Missouri River 340 with a college friend, and I’ve been hooked on endurance paddling ever since. Since then, I’ve completed some of the toughest long-distance events in North America, including the Missouri River 340, the Alabama 650, and the Suwannee 230. I also joined Operation Deep Blue, a six-day expedition from New Jersey to Washington, D.C., honoring fallen law enforcement officers and their families. For me, paddling is about more than just racing. It’s about resilience, healing, and pushing past limits — whether it’s paddling through the night, battling tough conditions, or simply finding joy in the small moments on the water. I go by the nickname “Penguin Viking,” because I try to bring both grit and humor into every challenge. My paddling philosophy is simple: every stroke forward is progress, no matter how small.”